Let me take you back to 2019, to the quiet, semi-urban town of North India. Life was going on as usual, but beneath the surface, a public health disaster was brewing.

One morning, a young man visited the local clinic, complaining of high fever, headache, and stomach pain. The doctor suspected it was a viral infection, a routine case. But as the days went by, more and more patients began showing up—each one with the same set of symptoms: fever that just wouldn’t quit, intense stomach pain, and extreme fatigue.

Before long, the number of patients swelled to 75, and the town’s health workers realized something much bigger was happening. These weren’t just isolated cases—they were witnessing an outbreak.

The Hunt for the Source

What could be causing this mysterious illness? The local health department sprang into action, conducting a thorough investigation. A sanitary survey revealed the root of the problem: a leaking sewage pipe had spilled waste into the town’s drinking water supply. The same water people had been drinking, cooking with, and using for daily activities had been tainted with dangerous bacteria.

That bacteria was none other than Salmonella typhi, the culprit behind typhoid fever. The town’s water was carrying this tiny organism from person to person, like a stealthy intruder, infecting them with enteric fever.

The Symptoms Unfold

Typhoid fever isn’t your average illness. It comes in slowly, insidiously— like a thief in the night, slipping through the defenses of the body, unnoticed at first but leaving chaos in its wake.

At first, it seems like nothing more than a mild inconvenience—a little fever, a headache, some stomach discomfort. But then it tightens its grip, day by day, rising stealthily like water in a flood. By the time you realize the danger, it’s already overwhelmed you, leaving you feverish, exhausted, and vulnerable to its destructive complications. It’s a silent invader that operates under the radar, but when it strikes, it hits like a hammer, hard and unforgiving.

Patients didn’t know what they were up against. Many suffered from severe abdominal pain, feeling like their insides were being twisted into knots. Some developed coated tongues, a telltale sign of typhoid, as if their mouths were cloaked in sickness. Others had rose spots—pink patches blooming on their skin, like a mark left by the disease itself.

For some patients, it wasn’t just a matter of feeling sick. The bacteria had invaded their bloodstream, like an army crossing enemy lines, spreading the infection to the liver, spleen, and gastrointestinal tract, putting them at risk of life-threatening complications like intestinal perforation or hemorrhage.

The Turning Point

Once the source of infection was identified, the public health officials acted quickly. They repaired the sewage leak and provided clean drinking water to the community. But stopping the outbreak required more than just fixing the pipes. It was a race against time to treat those who were already infected.

Doctors administered antibiotics like ceftriaxone and azithromycin to tackle the multidrug-resistant strains of Salmonella typhi, a growing threat in India. The patients received supportive care to manage their fever and rehydration for those suffering from diarrhea or vomiting. It was a fight on two fronts—against the bacteria inside their bodies and the unsanitary conditions outside.

Education played a big role too. Health officials went door to door, teaching families about the importance of boiling water, practicing good hygiene, and washing hands. They worked to ensure that even though the outbreak had started with a public health failure, it wouldn’t end with one.

The Aftermath and Lessons Learned

In the end, no fatalities were reported, thanks to the swift public health response and timely treatment. This outbreak was a wake-up call—not just for the town, but for everyone. It served as a reminder of how typhoid fever is like a hidden predator, waiting for the right conditions—contaminated water, poor sanitation—to pounce.

It also showed us that typhoid fever isn’t just a disease of the past. It’s still here, still affecting millions of people, especially in places where water infrastructure is weak, like a crack in a dam, ready to unleash devastation.

But this story also gives us hope. It shows that with the right tools—clean water, vaccination, education, and timely medical intervention—typhoid’s grip can be loosened, its spread halted. It’s a story of resilience, like a village rising from the ashes, where public health measures saved the day, proving that even the most insidious diseases can be stopped when communities and healthcare systems work together.

Typhoid Fever: Understanding a Silent Predator

In 2019, a quiet town faced a health crisis that many thought belonged in the past. Typhoid fever—an illness often overshadowed by other global diseases—reared its head, revealing how vulnerable communities can still be to this ancient foe. But what caused the outbreak, how does typhoid spread, and what can be done to prevent future cases?

This is the story of an outbreak, a bacteria, and a battle against time.

A Hidden Threat: The Cause of Typhoid Fever

Typhoid fever isn’t your average illness. It’s caused by the bacterium Salmonella typhi, a microorganism transmitted through contaminated food and water. Once inside the human body, it invades the gastrointestinal tract, quietly making its way into the bloodstream. Like a stealthy intruder, it spreads unnoticed at first, causing symptoms that seem minor: a headache, slight fever, or stomach discomfort.

But this bacteria isn’t here for a short stay. It tightens its grip, day by day, rising like a flood, bringing severe fever, exhaustion, and abdominal pain. When left untreated, it can cause serious complications—like a hammer striking—with the risk of intestinal perforation, hemorrhage, and even death.

In developing countries, where access to clean water and sanitation can be limited, typhoid thrives. This is not just a disease of the past. Today, typhoid fever remains a global health concern, As of 2019, an estimated 9 million people get sick from typhoid and 110 000 people die from it every year (World Health Organization). Most cases occur in regions with poor water sanitation systems, making the disease especially common in parts of Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

How Typhoid Spreads: The Silent Carrier

Typhoid fever is primarily transmitted through contaminated water or food, often due to poor sanitation or inadequate hygiene practices. One of the unique features of typhoid is that humans are the only reservoir. The bacteria live and multiply in the intestines and bloodstream of infected individuals and are excreted in their urine and stool.

There are two main types of transmission:

- Waterborne transmission: In areas with contaminated drinking water—whether from a sewage leak, flooding, or poor infrastructure—typhoid spreads like wildfire. Drinking or preparing food with contaminated water introduces the bacteria into the body, leading to widespread infection.

- Fecal-oral route: Typhoid can also spread when infected individuals prepare food or share utensils without proper hand hygiene. This makes secondary transmission in households or crowded communities particularly concerning.

Epidemiology and the Impact of Resistance

In countries with strong water sanitation systems, typhoid fever is rare, with cases typically imported from endemic areas. However, in regions like India, it remains a major public health issue. According to one study, India recorded approximately 10 million cases of typhoid fever in 2021, making it the country with the highest burden of typhoid worldwide. (John H, 2023) One growing concern is the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains of Salmonella typhi. These strains are resistant to traditional antibiotics like chloramphenicol, ampicillin, and cotrimoxazole, making treatment more difficult and increasing the risk of severe complications and death.

The spread of MDR strains presents a major challenge for healthcare systems, as patients often require stronger, more expensive antibiotics, such as ceftriaxone or azithromycin, to effectively treat the disease.

Clinical Presentation: The Slow Burn of Typhoid Fever

The symptoms of typhoid fever typically begin insidiously. Patients may feel slightly unwell at first, with malaise, headache, and stomach discomfort. As the infection progresses, they develop a step-ladder fever, where the temperature rises gradually each day, often reaching a high plateau after 7-10 days.

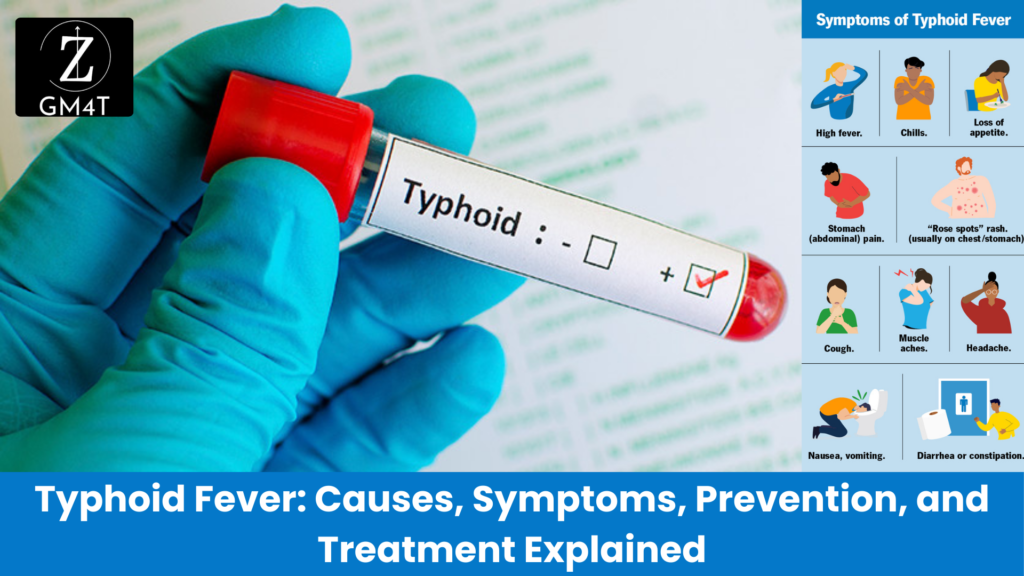

Key symptoms include:

- High fever, following a step-ladder pattern.

- Abdominal pain, often localized to the right lower quadrant.

- Coated tongue—a telltale sign of typhoid.

- Diarrhea (often in children) or constipation (more common in adults).

- Rose spots—faint, pink patches on the skin.

- Weakness and fatigue.

In severe, untreated cases, complications like intestinal hemorrhage and perforation may occur, requiring immediate medical intervention.

Diagnosis: Identifying the Stealthy Culprit

Typhoid fever is diagnosed through blood cultures, which isolate the Salmonella typhi bacteria from the bloodstream. This test is considered the gold standard and is most effective during the first week of illness. In addition to blood cultures, serological tests like the Widal test may be used, though they are less reliable in endemic areas where previous exposure to the bacteria can skew results.

In outbreak scenarios, bacteriological testing of water supplies is crucial. Identifying contaminated water allows public health officials to take swift action, repairing leaks and ensuring that clean drinking water is provided.

Treating Typhoid Fever: A Race Against Time

Once diagnosed, typhoid fever requires immediate antibiotic therapy. In areas where antibiotic resistance isn’t a major concern, fluoroquinolones like ciprofloxacin are commonly prescribed. However, in regions where MDR strains are prevalent, treatment typically involves third-generation cephalosporins like ceftriaxone or azithromycin.

Early treatment is essential to prevent complications, and supportive care, such as hydration and nutritional support, is often necessary, particularly in severe cases. In some individuals, the bacteria can persist in the gallbladder, leading to a chronic carrier state where they continue to shed the bacteria in their stool long after recovering from the acute illness. Chronic carriers may require long-term antibiotic treatment or cholecystectomy (gallbladder removal) to prevent ongoing transmission.

Prevention: The Key to Stopping Typhoid Fever

While treatment is vital, the prevention of typhoid fever is the true long-term solution. There are several public health measures that can drastically reduce the incidence of the disease:

- Sanitation and hygiene: Access to clean water and proper sewage disposal are critical. Communities must be educated about hygiene practices like handwashing, boiling water, and proper food preparation to prevent transmission.

- Water treatment: Chlorination, boiling, or using water filtration systems can make drinking water safe and prevent outbreaks.

- Vaccination: In endemic areas, typhoid vaccination is an effective preventive measure. The Vi polysaccharide vaccine and the Ty21a oral vaccine provide protection for up to three years and are recommended for high-risk populations, including travelers and those living in regions with frequent outbreaks.

The Takeaway: Typhoid Fever is Still Here, and We Must Act

Typhoid fever remains a global health challenge, particularly in areas with poor water infrastructure and sanitation systems. The story of this outbreak serves as a reminder that clean water, vaccination, and public health interventions are the key tools in fighting this disease.

As researchers, healthcare professionals, and future doctors, we must remain vigilant in our efforts to control and prevent typhoid fever. Only by improving sanitation, addressing antibiotic resistance, and expanding vaccination efforts can we truly loosen typhoid’s grip on vulnerable populations and ensure a safer, healthier future.